What are PFAS?

PFAS is an acronym for a class of toxic man-made chemicals called per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

PFAS contain chains of carbon and fluorine atoms, which together form one of the strongest bonds in nature. Because the bonds are so strong, PFAS don’t break down easily, causing them to build up in the human body and the environment. Thus, they have come to be known as “Forever Chemicals.”

PFAS chemicals have grown into a class of over 12,000 chemicals, which include older long-chain chemicals such as PFOA and PFOS, and newer chemicals made of short-chain bonds such as GenX.

PFOA and PFOS are two of the oldest and most studied PFAS chemicals and were phased out of production in the U.S. by 2015 due to concerns about health risks at ultra-low levels of exposure. However, they are still being used in production outside the U.S. and have become major contaminants in our environment and drinking water due to historical use.

After years of inaction, on September 6, 2022, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) finally designated PFOA and PFOS as “hazardous substances” under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA), also known as the Superfund law.

CERCLA provides the federal government with statutory authority to investigate, monitor and respond to hazardous substances that have been released or are under threat of release, into the environment. CERCLA also provides an enforcement mechanism for the government and private entities to hold parties responsible for cleanup costs if they are found to be liable for the release of substances (a) specifically designated as hazardous substances under CERCLA or (b) determined to present an “imminent and substantial danger to the public health or welfare.”

According to an EPA press release: On March 14, 2023, EPA announced the proposed National Primary Drinking Water Regulation (NPDWR) for six PFAS including perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA), hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA, commonly known as GenX chemicals), perfluorohexane sulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorobutane sulfonic acid (PFBS). The proposed PFAS NPDWR does not require any actions until it is finalized. EPA anticipates finalizing the regulation by the end of 2023. If fully implemented, EPA expects that the rule will prevent thousands of deaths and reduce tens of thousands of serious PFAS-attributable illnesses.

History of PFAS

The first PFAS was accidentally invented in 1938 by DuPont chemists, who were conducting research to find new chemicals that could be used as refrigerants. They stumbled upon an unusual coating during their experimentation. Testing revealed that the new substance, PTFE (polytetrafluoroethylene), was chemically very stable and had a remarkable ability to repel water and oil.

PTFE was soon used in the Manhattan Project during World War II because it could resist corrosion from fluorine in the gaseous diffusion process used to enrich uranium.

After World War II, DuPont began successfully marketing this substance in a product called “Teflon”, which was and still is used to make cookware that is slick and non-stick, and for water and stain-resistant fabrics.

In 1952, 3M discovered its own PFAS chemical, PFOS, when its chemists were trying to develop a rubber that wouldn’t deteriorate when exposed to jet fuel. During the experiments, some of the new substance was dropped on a laboratory assistant’s tennis shoe. When the assistant tried to clean the substance from her shoe, she discovered that it was impervious to water and alcohol. 3M began marketing the new material in 1956 as “Scotchgard”.

Development of these chemicals increased after a deadly fire aboard a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier, the USS Forrestal, in 1967. The fire resulted from the accidental launch of a rocket that caused a blaze that nearly destroyed the ship, killing more than 130 people. Soon after this tragic accident, manufacturers and scientists developed PFAS-containing firefighting foam, or aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) — a foam mixture that rapidly extinguishes fire.

The PFAS allows the foam mixture to spread, making it highly effective against petroleum fires and other flammable-liquid fires when mixed with water. PFAS-containing AFFF was then installed on military and civilian ships, airplanes, and airports. You may have heard radio commercials about mounting lawsuits by individuals exposed to AFFF, who later developed multiple types of cancer.

Fast forward to the 21st century… Until recently, the PFAS chemical PTFE, used in manufacturing Teflon, was manufactured using PFOA. But since 2013, the Teflon brand has manufactured PTFE without PFOA due to the U.S. phase-out of PFOA.

GenX chemicals are now being used in place of PFOA for much PTFE production. So when you replace one toxic PFAS chemical for another toxic PFAS chemical, the end result is that nothing has really changed. No better. No safer.

And the very sad part is that corporations will work to take advantage of consumers’ lack of understanding of the complexities of this class of thousands of toxic chemicals. They will greenwash, mislead and try their best to trick consumers into thinking their products are safe.

When you see something advertised as “PFOA-free” or “PFOS-free”, but not actually PFAS-free, know that it still likely contains other toxic PFAS chemicals.

PFAS chemicals have been around for over 75 years and the number of applications continues to grow. We are exposed through the water we drink, the food we eat, the products we use, the clothing we wear, and the air we breathe. PFAS contamination of our bodies and the environment is now recognized as an urgent problem in need of solutions.

But the tide is beginning to turn. Mounting regulatory action on the state level and lawsuits have caused 3M to announce in December 2022 that the corporation would stop manufacturing PFAS by the end of 2025. 3M is named as a defendant in over 3,500 PFAS-related lawsuits, exposing it to 31 potential liabilities of up to $30 billion, according to Bloomberg Law.

Health Risks of Exposure to PFAS

As previously stated, PFAS chemicals are considered dangerous at ultra-low levels. We often see Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCL) for chemicals in drinking water set to parts-per-million (ppm), or even parts-per-billion (ppb). PFAS can cause harm in the parts-per-trillion (ppt). To visualize this, imagine one drop in an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

PFAS are carcinogens and endocrine disruptors that are linked to a myriad of health harms.

Current peer-reviewed scientific studies have shown that exposure to certain levels of PFAS may lead to:

- Reproductive effects such as decreased fertility or increased high blood pressure and higher risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women.

- Developmental effects or delays in children, including low birth weight, accelerated puberty, bone variations, or behavioral changes.

- Increased risk of some cancers, including prostate, kidney, and testicular cancers.

- Reduced ability of the body’s immune system to fight infections, including reduced vaccine response.

- Interference with the body’s natural hormones.

- Increased cholesterol levels and/or risk of obesity.

- Increased risk of Type 2 diabetes in women.

- Changes in liver enzymes.

The science is so strong that even our own Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has acknowledged the health harms.

How and Where Are We Exposed to PFAS?

Current research has shown that people can be exposed to PFAS by:

- Working in occupations such as firefighting or chemical manufacturing and processing.

- Drinking water contaminated with PFAS.

- Using cookware coated with Teflon nonstick surfaces.

- Eating certain foods contaminated with PFAS, including fish caught in U.S. waterways.

- Swallowing contaminated soil or dust.

- Breathing air contaminated with PFAS.

- Using cosmetics, personal care, household cleaners or other products made with PFAS or that are packaged in materials containing PFAS.

Environmental Pollution from Cradle to Grave

PFAS chemicals and products made with them have left an enormous legacy of toxic pollution, from production through disposal. How did we get here?

Corporations like DuPont, found guilty of intentionally dumping PFAS into public waters, poisoned tens of thousands of residents in Parkersburg, West Virginia, for decades while covering up what they knew about the health harms. The story was told in the 2018 documentary, The Devil We Know, and dramatized in the 2019 film, Dark Waters, starring Mark Ruffalo.

WATCH the full documentary, THE DEVIL WE KNOW

WATCH the trailer for the film, DARK WATERS

Here are some examples of the devastating environmental impacts of corporate irresponsibility and regulatory inaction:

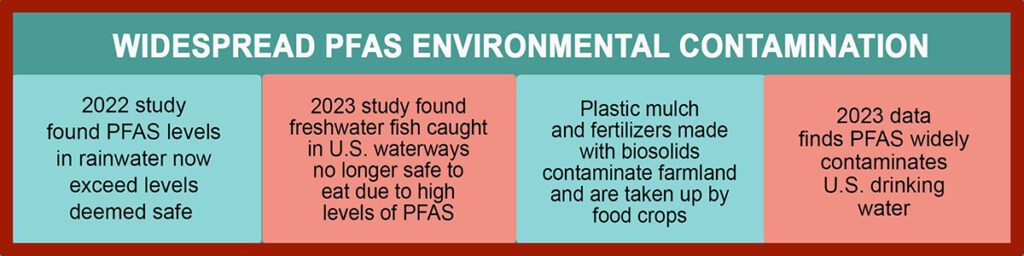

- PFAS forever chemicals are being spread globally in the atmosphere and as a result they are found at unsafe levels in rainwater and snow in even the most remote locations on Earth.

- Lakes and streams across the U.S. are polluted with PFAS, making locally caught freshwater fish too dangerous to eat.

- The common practice of using biosolids (sewage sludge) as fertilizer on conventional farms has caused widespread contamination of soil throughout the U.S. PFAS have been found at dangerous levels in cows and their milk, and in fruits and vegetables, even on organic farms that have converted from conventional practices. (Note: Biosolids are not allowed in organic agriculture.)

- Recent data finds PFAS widely contaminates U.S. drinking water.

Consumer Applications of PFAS

The growing number of commercial PFAS applications makes it nearly impossible to identify and cover them all. Common and known uses include:

Teflon non-stick cookware

Nonstick cookware became all the rage with the introduction of Teflon circa 1945. PFAS nonstick cookware is also sold under other brand names such as Anolon, Autograph, Calphalon, Circulon, Cuisinart, Dura-Slide, Eclipse, Eterna, GraniteRock, Granitium, certain Greblon pans, HexClad, ILAG, Quantum 2, QuanTanium, HALO, Ozeri Stone Earth, Skandia, Stratanium, Swiss Diamond, T-fal, Xylan and others that we may have missed. The non-stick surfaces are made with PTFE, a toxic PFAS chemical. (Note: Some brands, such as Greblon, may offer other types of pans made without PFAS).

Food

There are a number of ways that PFAS can make their way into food. Because of their barrier-type properties, PFAS are often used in a number of food-related applications. PFAS are used in food packaging for their grease, oil, and water-resistant properties.

PFAS have been found in certain:

- Microwave popcorn bags

- Takeout food packaging such as pizza boxes, hamburger wrappers, french fry containers and “compostable” bowls (which should never be composted – they will contaminate your soil)

- Paper plates, cups and bowls

- Parchment paper and paper baking cups

- Dry cat and dog food bags

- Foods such as ketchup, mustard and mayonnaise packaged in PFAS-coated HDPE plastic containers

In addition to contamination from packaging, there are other ways PFAS can contaminate the food we eat. The equipment used in food processing may be coated with a nonstick surface made with PFAS, or the chemicals used to oil or clean the equipment may contain PFAS. In both cases, it is possible for the food to be contaminated with PFAS during cooking, processing or packaging.

And disturbingly, a study found PFAS can be directly taken up by plants through their roots. As a result, crops grown in contaminated soil may contain PFAS.

Fertilizer and compost made with sewage sludge, also marketed as biosolids, contain PFAS that contaminate soil. Fertilizer and compost made from waste streams that include PFAS-containing “compostable” bowls and paperware will also be contaminated.

Farms using PFAS-containing plastic mulch and tarps may also leach the chemicals into the soil and then be taken up by the crops.

Cosmetics and personal care products

PFAS have been used in cosmetics to create long-lasting waterproofed products that can continue to look fresh for as long as a full day after application. PFAS chemicals have been detected in an incredibly wide range of cosmetics and personal care products, including certain body lotions, body oil, foundation, concealer, blush, cuticle treatment, eye cream, eye pencils, eye shadow, brow products, hair creams, anti-frizz cream, lip liner, makeup remover, anti-aging cream, mascara, moisturizer, bars of soap, shampoo, conditioners, nail polish, nail strengthener, powder, hair spray and mousse, lip balm, lipstick, skin scrub, shaving cream, and sunscreen. Scientists even found one PFAS compound in a hand sanitizer.

Other personal care products that have been recently tested are dental floss and tampons, where organofluorine, an indicator of PFAS, was detected in several of the products tested.

You may wonder why we should be concerned about PFAS chemicals present in products we don’t directly consume. Dermal absorption – absorption through the skin – is likely.

Clothing and outdoor gear

PFAS are used to create waterproof and stainproof fabrics, often advertised as “water or stain-resistant”, or “waterproof” or “water repellant,” “wrinkle-free,” “wrinkle-resistant,” “dirt-repellant” and/or “DWR” (durable water repellent). Products advertised or labeled with these claims are likely made with PFAS.

The chemicals are applied to the fabric surface to create a barrier against stains, dirt and water, or are used to create a membrane that makes rain gear more “breathable”. As the barrier or membrane breaks down, the chemicals can end up in the air and be inhaled, or on surfaces where they can be ingested.

Some PFAS-treated fabrics are sold under the brand name Gore-Tex for rainwear, hiking and outdoor gear and for moisture wicking, but there are many more that are made with PFAS but aren’t Gore-Tex.

PFAS have been detected in certain:

- Children’s school uniforms, women’s period underwear, workout clothing such as leggings and yoga pants, shoes, outerwear, boots and even flannel shirts.

- Baby textiles including bibs, pajamas, raincoats, hats, mattress pads and covers, waterproof play yard sheets, changing pads

- Baby gear such as car seat covers and strollers

- Outdoor gear such as ski wax, bicycle oil, climbing ropes

- Firefighter’s uniforms

Bed Mattresses and Linens

PFAS have been detected in certain crib and other mattresses, stain-resistant comforters, sheets, pillow protectors and mattress protectors as well as tablecloths and napkins.

Other products that may contain PFAS

- Fire-fighting foam (AFFF)

- Stain-resistant furniture and carpeting, sometimes under the brand name “Scotchgard”

- Appliances with fingerprint-proof surfaces

- Touch screens on cell phones and tablets

- Shower doors with water spot-resistant protective coatings

- Pesticides

- Fertilizers and composts, including those meant for home garden use, such as those made from biosolids (sewage sludge) or from waste streams that include PFAS-containing “compostable” bowls and paperware

- Car wash protective coatings

- Artificial turf

- Guitar strings

- Ski wax

Regulatory Failures and Legislative Successes

The EPA has begun to address the need to regulate PFAS with proposed regulations. One of the problems however, is that the agency has chosen to focus on a small number of PFAS chemicals, a very tiny fraction of the 12,000+ chemicals currently in use.

While this is a step in the right direction, it does a woefully inadequate job of addressing the problem.

Though our federal agencies have been very slow to act, states and cities have begun to step up to provide protections.

Since 2021, California, Connecticut, Maine, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Washington have passed laws banning PFAS in food packaging. California’s law also forbids manufacturers of cookware to label their products as free of any particular toxic chemical if the pots or pans contain any substance in the same class of compounds as the toxic chemical.

California, New York and Washington banned PFAS in clothing, while multiple states are prohibiting PFAS in other textiles, such as carpets or furniture upholstery, or in children’s products like car seats and strollers.

California, Colorado and Maryland banned PFAS in all cosmetics and personal care products.

At least 15 states have banned or limited the use of firefighting foam with PFAS because it is a major source of water pollution.

Maine has gone several steps further with a ban on all non-essential uses of PFAS. Maine also banned the use of composts and soil amendments made from biosolids.

New artificial turf fields have been banned by Boston, and various municipalities and states have considered bans on artificial turf including Massachusetts, Arizona, and California.

The momentum continues in 33 states where legislation has been introduced. Vermont’s Senate unanimously approved a ban on the chemicals in cosmetics, textiles and artificial turf.

Does Organic Certification Protect Against PFAS Exposure?

The short answer is, unfortunately, no.

While organic regulations prohibit the use of thousands of synthetic chemicals and pesticides, the class of PFAS chemicals is not included. We’re not sure why PFAS have escaped organic regulations, but we have begun to advocate for their removal.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

- Click and send an email to the White House and Congress demanding a ban on all non-essential uses of the entire class of PFAS chemicals. We’ve made it quick and easy to do. Take a minute to edit the comment text to make it your own if you can. CLICK HERE.

- Currently, it is nearly impossible to avoid all PFAS exposures. Follow these guidelines and do your best.

- Cook with stainless steel, glass or cast iron cookware. Avoid Teflon and PTFE-coated nonstick cookware.

- Drink filtered water. Reverse osmosis is the most reliable filtration method to remove PFAS. Our favorite RO systems are Waterdrop’s tankless under-the-sink systems.

- Avoid takeout food cups and packaging – especially for hot food and beverages – by bringing your own. Use stainless steel, ceramic or glass.

- Look for the Made Safe certification on personal care products & cosmetics, clothing, bedding, household and pet products. You can find all Made Safe certified products HERE.

- If you farm or garden, avoid fertilizers and composts made from biosolids. Many municipalities offer free compost – these products are likely made from biosolids. Ask before you use.